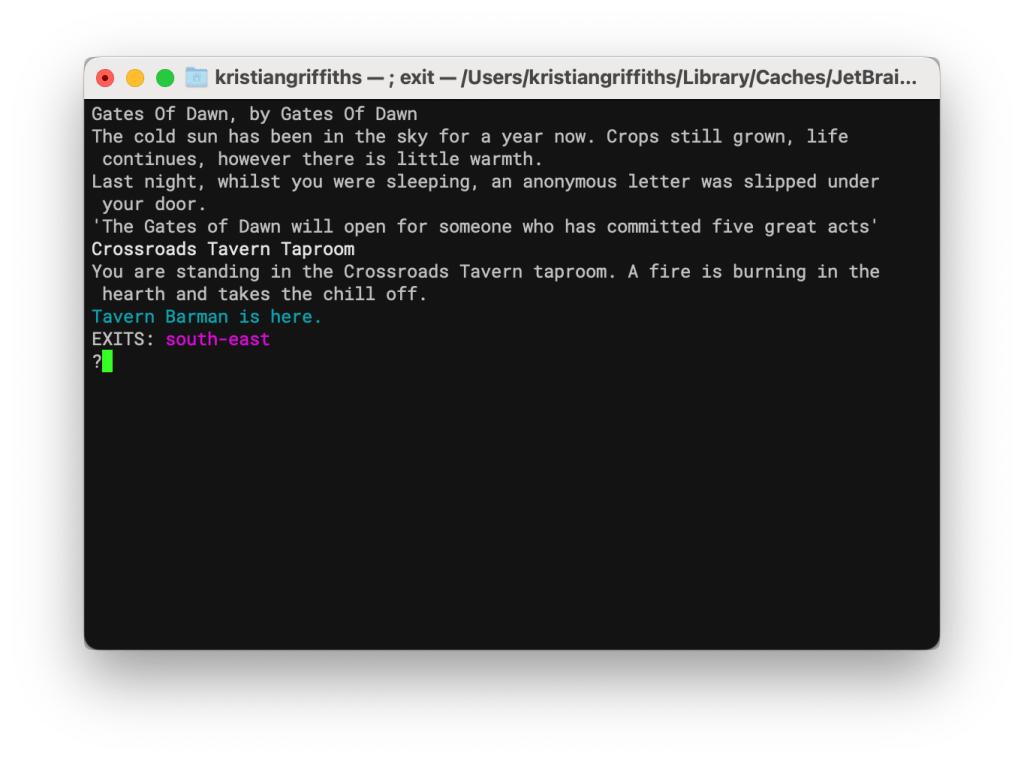

In this part, I’m going to highlight the structure of the Core Game and how that works.

Core Game Structure

As a refresher: the core engine, called Penguin Core, contains all the mechanics for text parsing, game state and traversal. It also contains the entities used to represent the game world. It is a .NETstandard 2.1 project (.NET 6 wasn’t here when I started it).

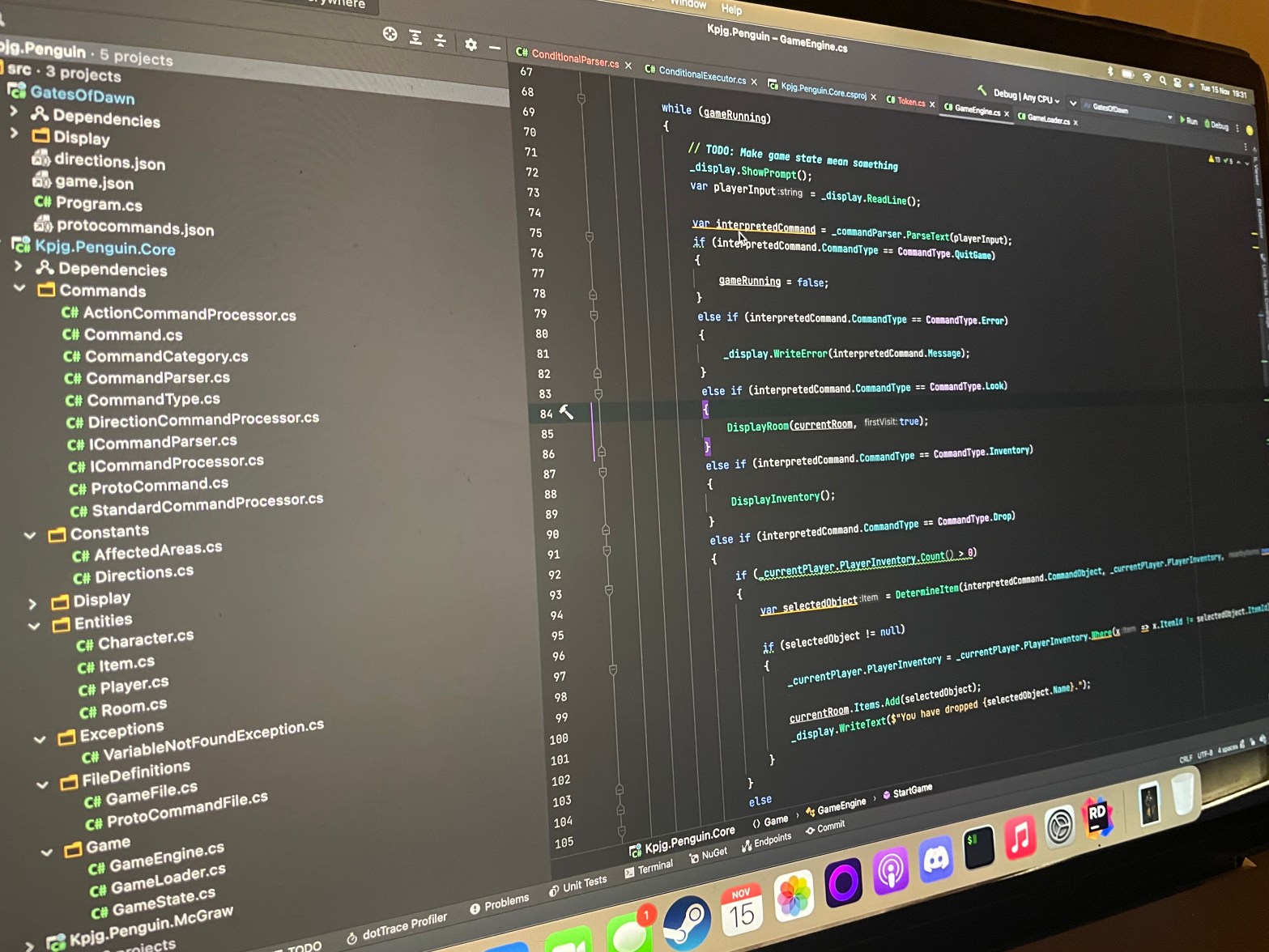

As with all of my projects, files are organised based on what they are. So Commands, Constants, Entities, Exceptions, FileDefinitions and the ever helpful “Game” folder.

Game

The Game Folder contains the heart of the engine. It has the Game Engine itself, a class that represents the Game State, and the Game Loader that knows how to turn the json and script files into a real game.

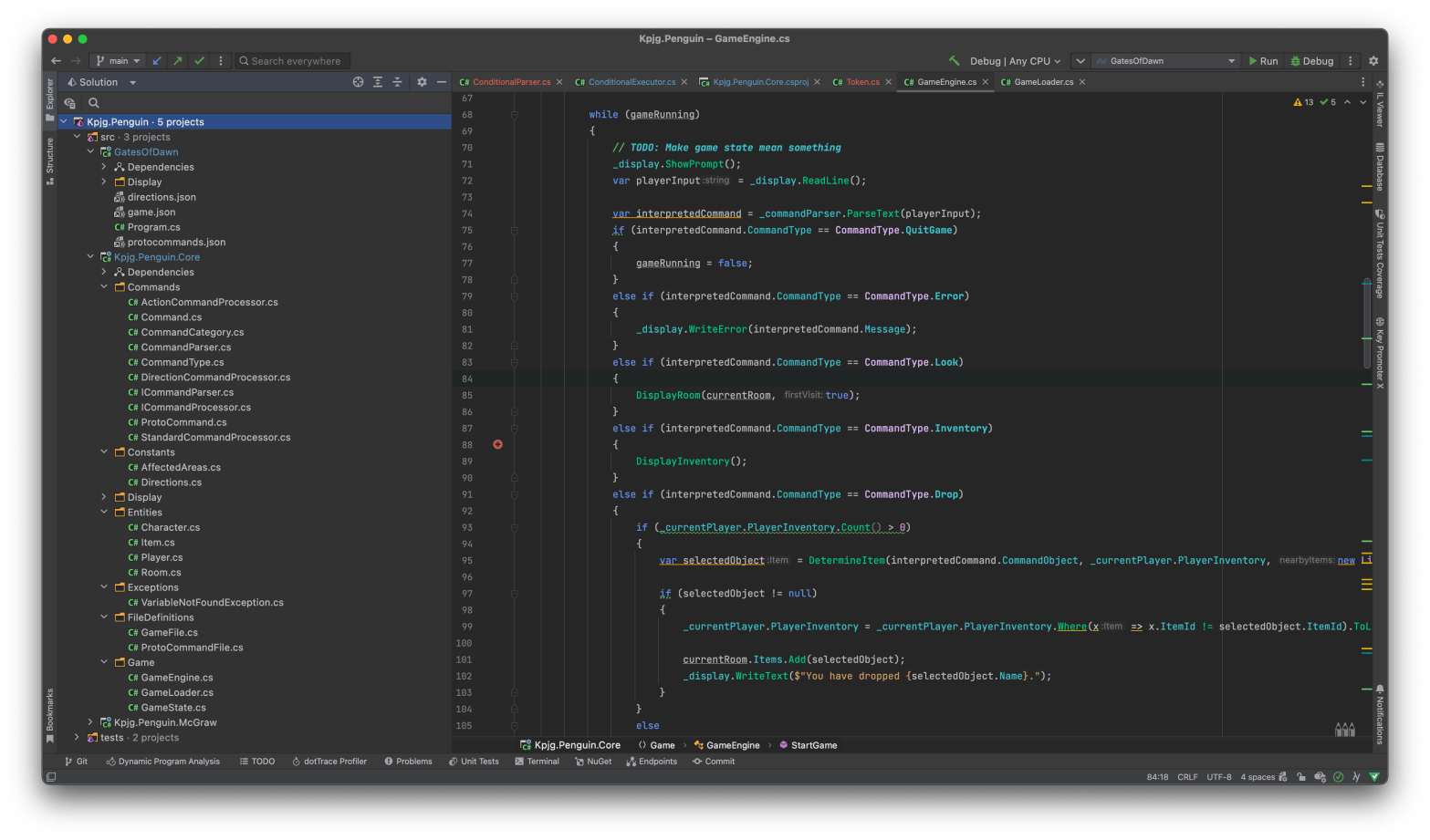

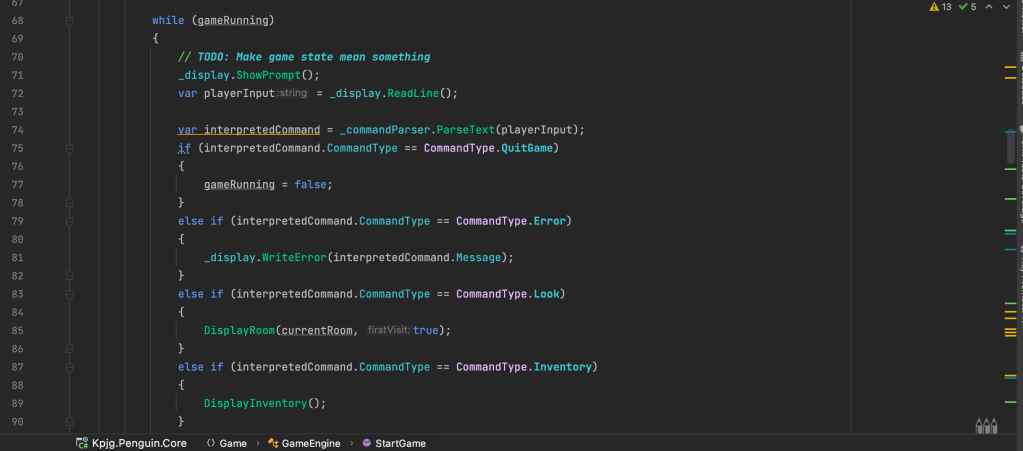

Most games follow a pattern of accept input, update game state, display. This game is no different in some ways, although accept input is a blocking operation. Nothing happens “in the background” on this game (it’s not a MUD, however much I want it to be). The GameEngine class implements this game loop.

The idea is that you have you game-specific code that creates a new instance of the GameEngine, giving it an instance of IDisplay that is how you want data to be shown on the screen. It also requires an implemented ICommandParser (one of which is available within the Core Project) that is used to turn text into game actions.

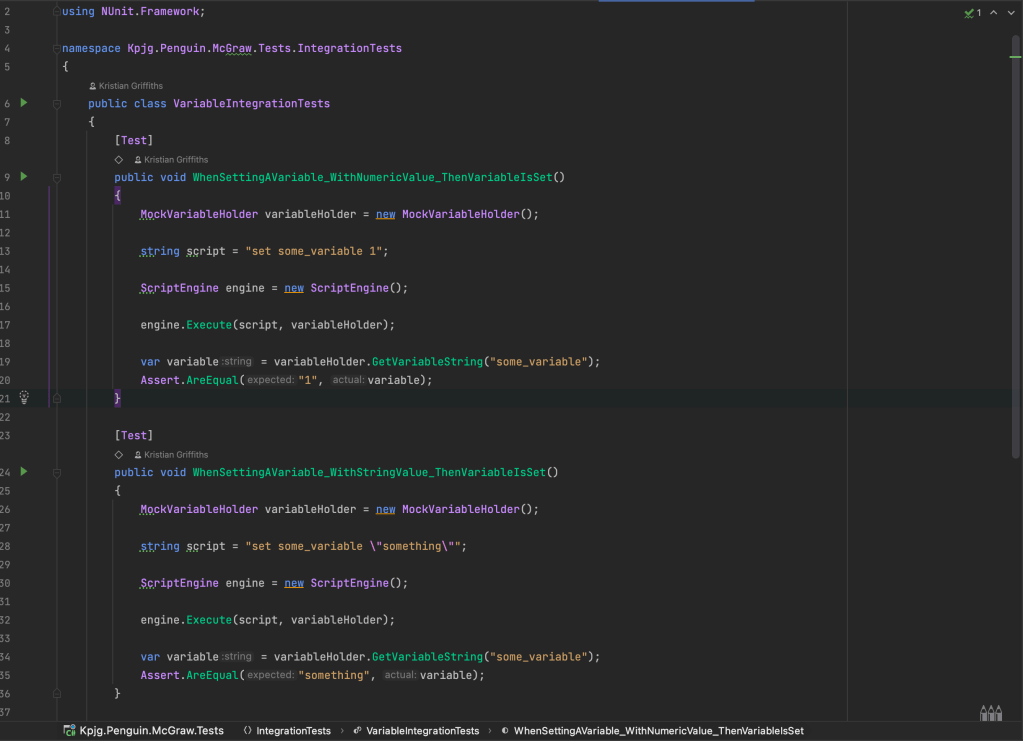

The Game Loader is responsible for parsing the Json file and converting it into game entities. The game loader also parses the game scripts into IExecutors, the “compiled” form of the raw script, making sure that we’re not performing this interpretation of the scripts on the fly. (Note: it is an assumption on my part that this will be slow, as scripts are evaluated on every “turn”).

Finally the GameState is a Script Engine compatible variable bag that can be given to the script engine to have the global variables updated, but it will also have some of its own game logic in there as well (I haven’t decided what yet).

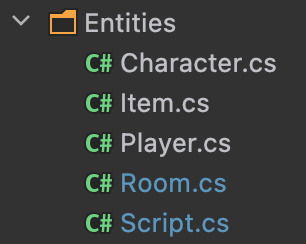

Entities

The other set of elements I’ll cover today are the Entities in the game, this is how we represent the game world.

It’s kept very, very simple. Starting with the obvious one, Rooms, these are the locations a player can be within. A room can contain items and characters. A room has exits (north/south/etc). A room has a description and a quick description for when you’ve already visited it and don’t need the flowery text anymore. Rooms have names, and Ids. Finally, rooms also have scripts for certain scenarios: on entry (or on first entry) and on leave. These scripts should be able to prevent the player from leaving based on “some thing” being true.

Items can either be in rooms or in a player’s inventory. As an extension, I’d like characters to have items in the future and be able to give them to players or be steal-able (dependent on the game, of course).

Items are special, however, as items can have special actions done to them. These actions are defined in a protocommands.json file, which (again) I’ll go through in the future, however suffice to say it means you can have custom commands for items such as lick, punch or tear if you so wish it.

The player is an extension of a character, the difference being a player has an inventory.

Script objects are used to have the ScriptLocation within it and the compiled executors. It’s mostly a DTO for use within other objects.

Progress Update

This last week’s been quite a good one for progress. I’ve integrated the scripting engine into the core game engine, so now every time the world updates “global scripts” will run. The next elements I need to add in are the onentry/onleave on rooms, as well as potentially “on leave in direction” which would mean you can’t go a certain way unless you fulfil specific criteria.

I also believe that I’ll need to make characters talk, or make things be said by the “narrator” when you try and move north and you don’t have an apple in your inventory.

I’m also looking to get this code up on Github soon so you can see my progress as I do it. I currently host it in a private bitbucket repo, however I don’t intend to release this game or make money on it. It’s all for fun.

Next time I’ll cover the text parser and custom actions.