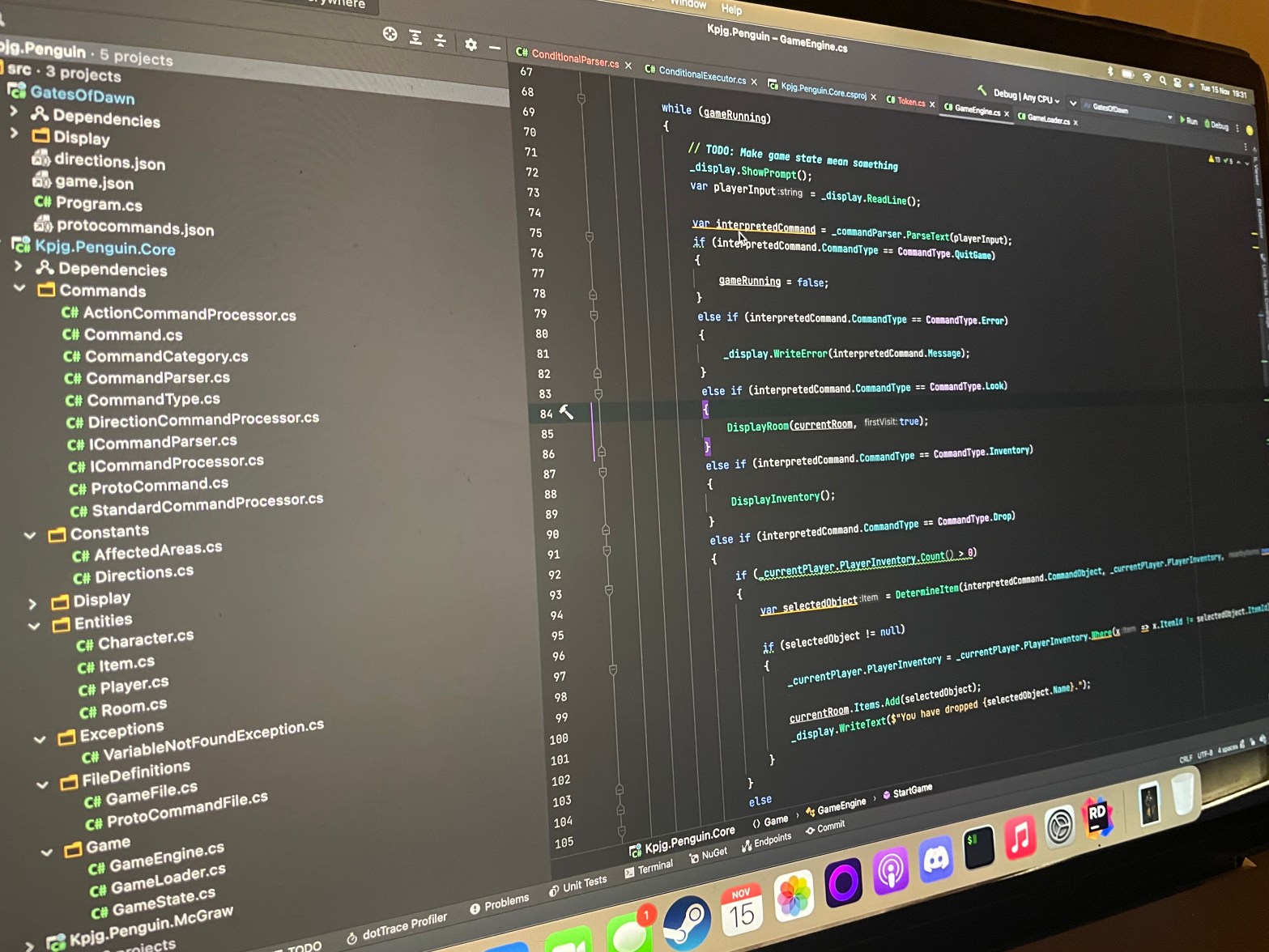

In this second part of this series on my text-based adventure, I’m going to cover the scripting language: what it is and why did I do it?

Background

As mentioned in the previous post, I originally had no intention on writing a full on scripting language. As I had initially created an engine that would allow for rooms, items and actions to exist, I realised there was no game state, and that I had to way of changing the state of the world based on either triggers and variables. Almost all games have the concept of a world or game state, with some variables that are checked to evaluate if, for example, the game has been “won” or for more complex games, whether a series of variables or conditions are true to trigger some pre-scripted event (I’m oversimplifying here). If I didn’t have some means of doing this, my game would be a walking simulator. A text-based walking simulator.

In order to allow some interactivity in the world and have a story that allowed for some branching paths I would need some way of saying “when this happens do this”.

I could have integrated these elements into the C# code. Created a fully scriptable game where the rooms are defined in C# as is the “what do you do when this happens” however that didn’t fit with my idea of a re-usable engine where the game executable had display logic but the game itself was in separate files that could be modified without need a recompile of the binaries.

First Idea

My first Idea was to have some json structure that allowed for basic conditionals using a variable bag. For example:

{

"onenter": [

{

"condition": "eq",

"leftbit": "somevariable",

"rightbit": 23,

"then": {

"print": "Oh no!"

}

}

]

}This, to me, felt incomplete and a bit messy. I was trying to get json to do things that start to become unreadable, especially with larger expressions. I wanted something that a developer could recognise and use. I liked the idea of tokenising the expressions in the code into some format like the above, but I felt that if I were to do this, I’d want even more power and something that could be re-usable in other projects.

The Options

I had a number of options open to me when building out the scripting engine. The first option was to use an existing language and integrate it into my game. For this three things came to mind: Lua, Python and C#.

Lua – This option felt the best of the bunch. I liked the idea of integrating this well-rounded language. I had toyed with Lua before in very basic situations, however that was in C++. I’d never tried it in C#.

Python – As I’m rather a fan of python I considered using it as a scripting language. It works well, but I wasn’t sure of how to get started as having python embedded within C#. This option was quickly off of the table.

C# – I could also use C# itself, writing C# that is called within the C#. This was a thing I thought could cause the most problems, as without careful consideration there might be security considerations which, at this time, felt way above my pay grade.

My final thoughts on the matter were that I’m writing this game as a fun programming exercise, not to have something perfect or indeed marketable. By creating a finished product I will have the satisfaction of having completed something, however.

Syntax

So far you can achieve three things in the scripting language.

Setting a variable in the global variable store

SET Some_variable "hello"Passing printable output back to the executor

PRINT "Hello"Finally, a conditional:

IF Some_variable = "hello"

SET New_variable = "dogs"

END IFTesting

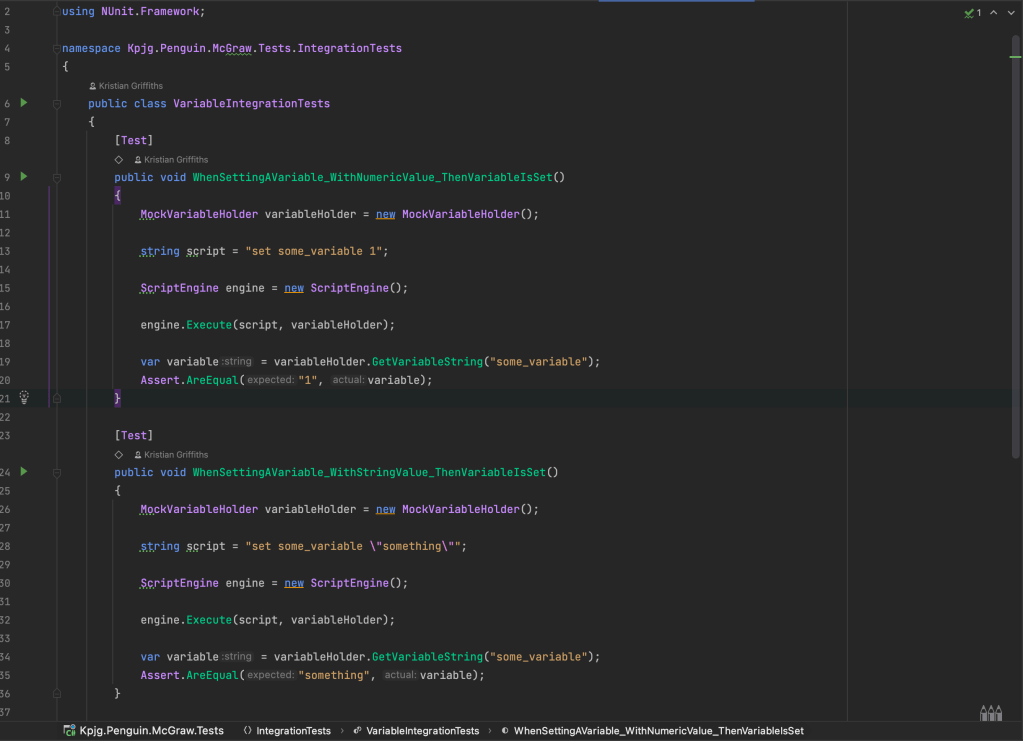

All tests in the project are Integration tests at this time. This was a deliberate decision to have these over unit tests as, from the outset, I wasn’t aware of what units I needed.

Integration tests are using nUnit, and follow the standard Arrange/Act/Assert pattern. Shown in the picture above are the Integration tests for the Set Variable operator.

These tests have proven invaluable to the development of the system, as these scripts get evaluated with an implemented variable bag, and minimal mocks. The setup of the items is done for real, with no mocks. This is to ensure the script evaluation is as real as possible.

Each of the three current operators have an integration test file. The test files also build on the previous ones. So SET VARIABLE relies on itself, PRINT relies on SET VARIABLE, as it is possible to print a variable to the screen, and IF relies on the other tests as variables have be set before they are evaluated.

Conclusion

Being honest, I’m still not sold on the idea of having my own Script engine. I’ve reached the part of this work that it’s starting to grind and I’m wondering if it’s too late to bring in Lua. I’ll power on as I think this makes it a much more interesting academic exercise and I recall, when I had first tried Lua, there was a really good reason.

I’ve not made any more progress this week than I had last week, however my intention over the next few weeks is to get the script engine finished and then start to implement some tooling to help myself build the game as at the moment I don’t think just having Json files is a good idea. I might want to extract the script files into their own thing and, importantly.