I’ve always been enamoured by Text-Based adventures. When I started my voyage into the world of programming at age 9, I started writing one using QBasic. I had no idea what a text parser was, each room was a subroutine in its own right, and as I made many mistakes I slowly learned how to program.

Then, many years later, I got a chance to play Westfront PC: The Trials of Guilder. It’s strange game, to say the least, but I loved it. The colours, the scope! There was a combat system; NPCs walked around. I had no idea what I was doing but I loved doing it.

That brings me to the present day. I have many side projects that I’ve pottered away on over the years, but one I’ve been revisiting with an idea to finishing it is a project I call Penguin (I name all of my projects after birds).

I’m assuming, from this point on, that you know what a text-based adventure game is, however if you don’t I’d recommend checking out Zork, or my absolute favourite by Emily Short: Counterfeit Monkey

The Goal

My initial goal was to write a text-based adventure on its own. No special engine, no re-usability, just tell a story. However as usually happens I thought: why not make an engine so you can make MANY text-based adventures. So the challenge was set and the goal became:

- Create re-usable text-based adventure engine agnostic of the platform it runs on (Penguin)

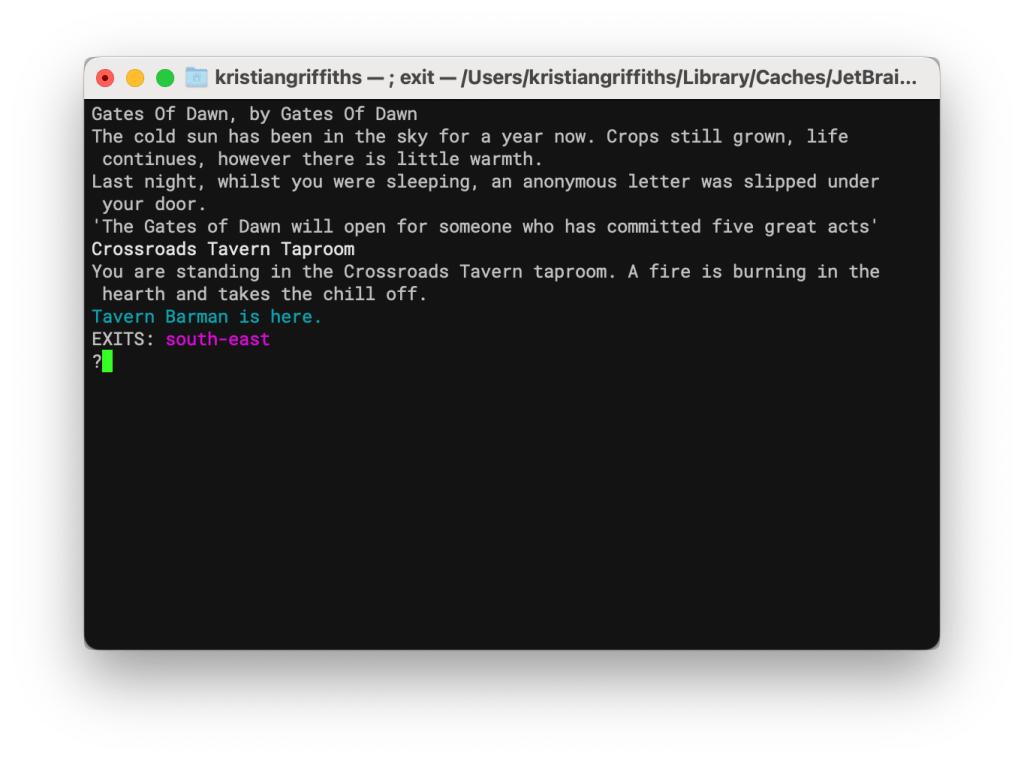

- Create a game (Gates of Dawn) that runs on that engine and implements the front end in a C# console application

- Ensure the game description language was human readable

Why not use Inform?

There’s already a really good (if not great) language and system for writing text-based adventures called Inform. Inform has language, IDE, design system, pretty much everything you need for producing top-class text-based adventures. Inform uses a near-natural language system for creating rooms, objects, story, etc.

The main reason I chose not to use inform is nostalgia. I spent most of my youth trying, and failing, to write one text-based adventure that was playable. I relied solely on the help files of QBasic to teach me about programming but I was lacking in some of the core concepts. Now as an adult and someone who has done software development in the past, I thought I should be able to have a good go.

Structure

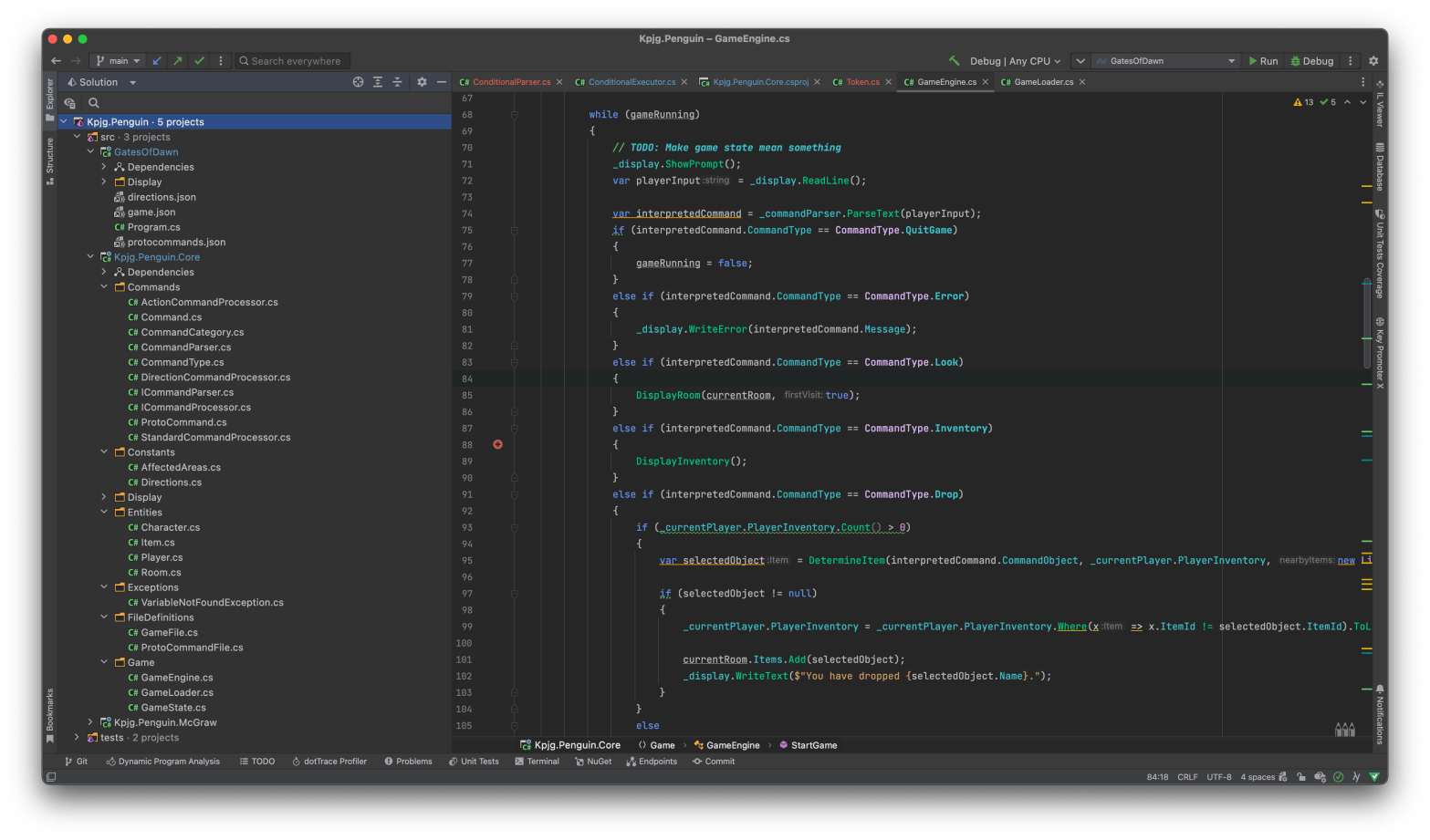

As previously mentioned the Penguin System is centred around the concept of a re-usable engine, so to make a game in Penguin involves a game library (in this case I’ve called it Gates of Dawn) and the engine itself.

The .NET solution has 4 parts to it:

- The game engine – Penguin

- The script engine – McGraw

- The game itself – Gates of Dawn

- Unit tests

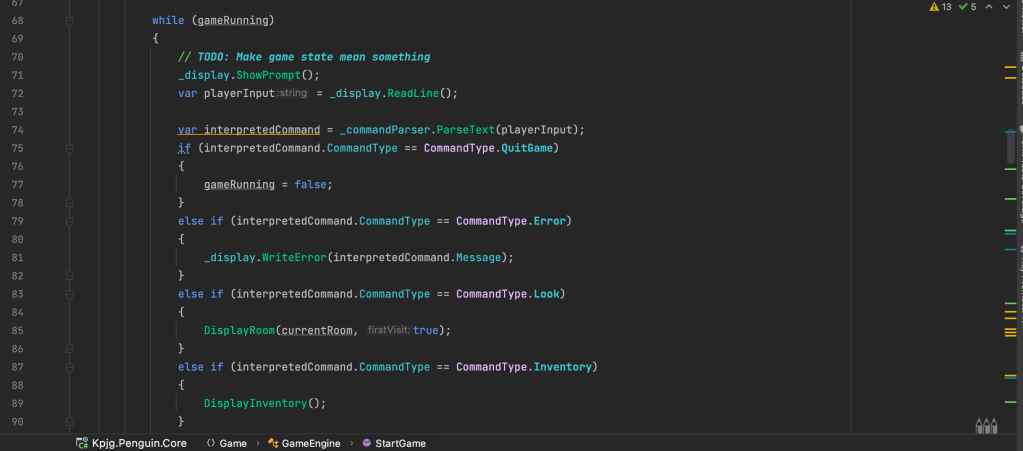

The game engine handles taking input, changing the world state based on that input, then telling the display implementation what to know on the screen. The engine can also call the scripting engine to evaluate scripts where needed.

The scripting engine handles evaluations that will produce output (either setting world variables or producing some output that’s intended to go the screen). The script engine has a whole host of things going on (and still in development at the moment) but the intention is for it to be able to handle a simple syntax.

The game portion contains the game data, any special commands the game has on top of the “standard” commands (and how to handle them). The game is also responsible for the implementation of the display engine. The current game implements the display engine as a console application, however the intention is for this to potentially be ported to MonoGame to allow for more interesting graphics (much like Inform and some game engines allow).

Games are (currently) json format and there is no plan to change that at this moment. The intention is, potentially, for someone happy enough to write a game implementation completely in JSON without ever needing anything else.

Challenges?

The biggest challenge is one of scope. When I set out to make the game I hadn’t intended to create the scripting side of the project (McGraw). I had thought, if I’d needed it, I could do some kind of expression thing in the json. It became clear, though, that this idea was too simplistic and wouldn’t allow me to tell a decent story and achieve an engine that supported rooms, dialogue trees and battles.

I evaluated a number of ways of doing the scripting, from using Lua in C#, to using C# itself within C#. That latter seemed dangerous and the former was using a library that seemed to not be complete. This made me nervous that I would have to come up with my own engine, then my own syntax. This was scope creep and given my remit to make a text-based adventure game within a re-usable engine was a large one, I now have to start limiting myself.

Another challenge is one of testing. Unit testing and integration testing in the project has really helped make sure that some of the mechanics work well, but it doesn’t beat loading up the game and seeing what’s broken. To start with the parser didn’t work in the slightest, which made me happy as I would’ve been worried if it had worked first try.

Current progress

So far we have the parser in place, able to traverse room to room. Items can be picked up and read, as well as dropped.

The script engine has been started with a syntax decided upon. Only three things are in at the moment: setting a variable in the global variable bag, sending some output intended to go on the screen back to the engine, and a simple if/equality operation (with an else).

What’s next?

I need to integrate the scripts into the game itself, which means some design decisions have to be made, as well as looking into pre-“compilation” of the scripts.